Michael Cherney: Those Waters Giving Way

讲座《那远去的江水》将于在艺平台直播。

欢迎扫描下方二维码进入直播间。

秋麦在虎跳峡拍摄

"One would be hard-pressed to find a “more Chinese” artist than Qiu Mai. Photographer, calligrapher, and book artist, Qiu Mai’s work is done with the great sophistication that draws on the subtleties of China’s most scholarly and esoteric traditions. Based in Beijing and a successful artist whose works have been collected by The Metropolitan Museum of Art’s Department of Asian Art, Qiu Mai’s art is less provocative than it is intellectually engaging, meditative, and often simply beautiful. What is provocative is his identity: Qiu Mai is the Chinese name for Michael Cherney, born in New York of Jewish parentage. Cherney’s work is the cutting-edge demonstration of artistic globalization: if Asian artists can so readily “come West,” then what is to prevent large numbers of future Western artists from “going Asian”? Or, like Qiu Mai/Michael Cherney, going both ways at once, both American and Chinese, modern and traditional. "

Jerome Silbergeld, P. Y. and Kinmay W. Tang Professor of Chinese Art History, Princeton University

Artist Statement

The appeal of traditional Chinese landscape painting is that works are intended only as hints at the potential that the real world has to offer; where the image lingers in a state between the manifest and the void. For more than a millennium a vocabulary of brushstrokes (along with the materials to support them) has evolved and been perfected for representing nature. But the English word “nature” has multiple meanings. There is the outward appearance of nature: that which one can observe; heaven and earth, or tiandi In Chinese. Then there are the inherent qualities: the nature, the characteristics of something, such as a rock, a tree, or even a person; in Chinese, this is ziran.

By focusing on and conveying the essence and energy of natural phenomena, a painting could feel more “real” than something like a photograph because it contains timeless qualities of nature beyond one unique moment. This approach to painting could rectify nature as much as depict nature.

So how can a photographer overcome this seeming impossibility for photography to convey the essence of traditional Chinese landscape painting, when a photograph is captured from a specific location at a specific moment? Well, given that the vocabulary of brushwork that informs Chinese painting was drawn from nature, one should be able to find it within nature, though it is usually hidden in the details.

Copying from nature or from masterworks has been an essential element of the Chinese landscape painting learning process, and photography certainly is copying. But a certain quality of observation is also required. My explorations come after having first spent time absorbing classical works. When wandering, a moment will arise and a visual trigger will occur that leads to the click of the shutter; the trigger can sometimes be subconscious. After traveling, back in the studio it becomes a matter of searching for qi within the frame.

My intention has been for the photographs to serve as a conduit for nature; for a world that can be touched. Altering the image would defeat the purpose, so I refrain from that. Only Nature may exaggerate herself.[i] This still leaves many tools that can be utilized, such as cropping, masking, enlarging, and folding.

My hope is to imbue photography with a sense of the rise and fall of the ten thousand things. Yet photography also allows the journey that leads the viewer through the depth of a piece to include a return via the realization that what is being seen is indeed light as it existed for a moment in the physical world, and thus offers a feeling of connectedness between the viewer, the physical world and its essence.

[i] Henry David Thoreau, A Week on the Concord and Merrimack Rivers, 1849.

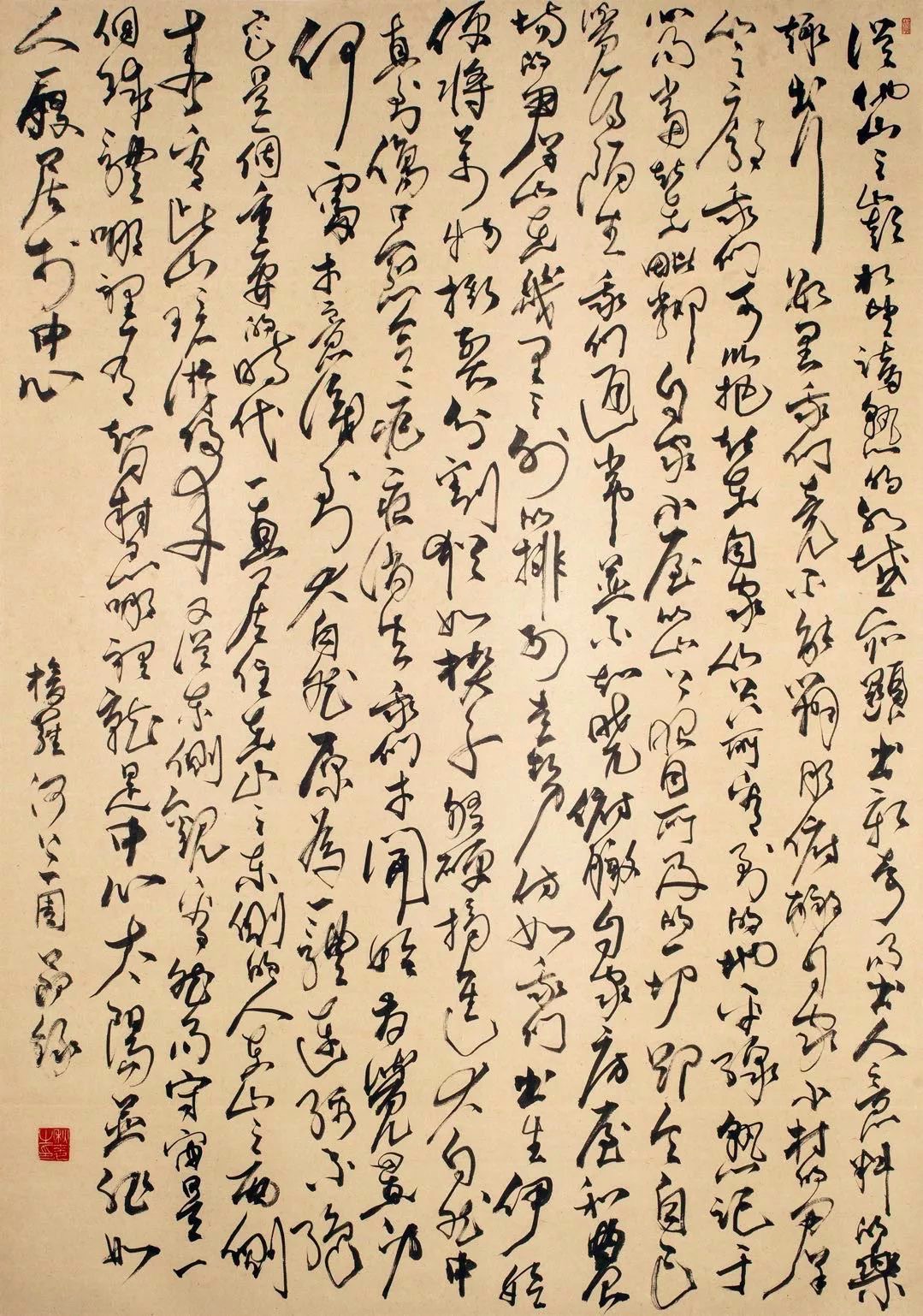

秋麦书法:梭罗《河上一周》节录

立轴,书法

232cm×106cm

2012

秋麦|Michael Cherney