RongRong's East Village in Contemporary Chinese Photography and Media Art exhibition at the Walther Collection.

Life and Dreams

Contemporary Chinese Photography and Media Art

May 13 – November 18, 2018

Curator

Christopher Phillips

Photography and Media Art by Ai Weiwei, Cang Xin, Cao Fei, Chen Lingyang,

Chen Shaoxiong, Cheng Ran, Hai Bo, Hao Jingban, Hong Hao, Hong Lei, Huang

Yan, Jiang Zhi, Sze Tsung Nicolás Leong, Lin Tianmiao, Liu Chuang, Lu Yang, Luo

Yongjin, Ma Liuming, Miao Xiaochun, Mo Yi, Mu Chen, Qiu Anxiong, Rong Rong,

Shao Yinong, Sheng Qi, Song Dong, Sun Xun, Bo Wang, Wang Gongxin, Wang

Jinsong, Wang Qingsong, Weng Fen, Xiang Liqing, Xu Yong, Yang Fudong, Yang

Yong, Zhang Dali, Zhang Hai’er, Zhang Huan, Zhang Peili, Zheng Guogu, Zhou Tao,

Zhou Tiehai, and Zhuang Hui

Contact: info@walthercollection.com

T: +49 731 1769143

E: info@walthercollection.com

Facebook.com/TheWaltherCollection

www.walthercollection.com

@walthercollect

Life and Dreams

Contemporary Chinese Photography and Media Art

The Walther Collection presents Life and Dreams: Contemporary ChinesePhotography and Media Art, the first extensive exhibition of works by Chinese artists represented in The Walther Collection. Featuring forty-four artists, Life and Dreams showcases a wide range of groundbreaking photography and media art produced by internationally recognized figures such as Yang Fudong, Zhang Peili, Ai Weiwei, Song Dong, Cao Fei, and Zhang Huan during an era of momentous social and economic change. It also incorporates new acquisitions and selected loans of significant media art by innovative younger artists such as Sun Xun, Lu Yang, and Qiu Anxiong to provide an up-to-theminute account of the main directions and key achievements in contemporary Chinese photography and media art during the past three decades. Curated by Christopher Phillips, Life and Dreams will open at The Walther Collection in Neu-Ulm, Germany on May 13, 2018, and is accompanied by a catalogue edited by Christopher Phillips and Wu Hung, co-published by Steidl / The Walther Collection.

Showing visually inventive and emotionally compelling artworks, the exhibition demonstrates the remarkable speed with which photography and media art have occupied important positions within the field of experimental Chinese art since the early 1990s. Throughout Life and Dreams, photographic works register artists’ responses to the sweeping social and economic changes that have fundamentally altered the face of China’s cities and transformed the fabric of everyday life. Featured selections of media art often evoke an ambiguous world of technological fantasy, suggesting where these changes may be leading the country and its inhabitants.

To highlight the underlying currents in contemporary Chinese artistic production, Life and Dreams contains five modular themes, which unfold throughout the three exhibition buildings of The Walther Collection. Together, these topics constitute an informal network of ideas and associations that link the works within the exhibition together.

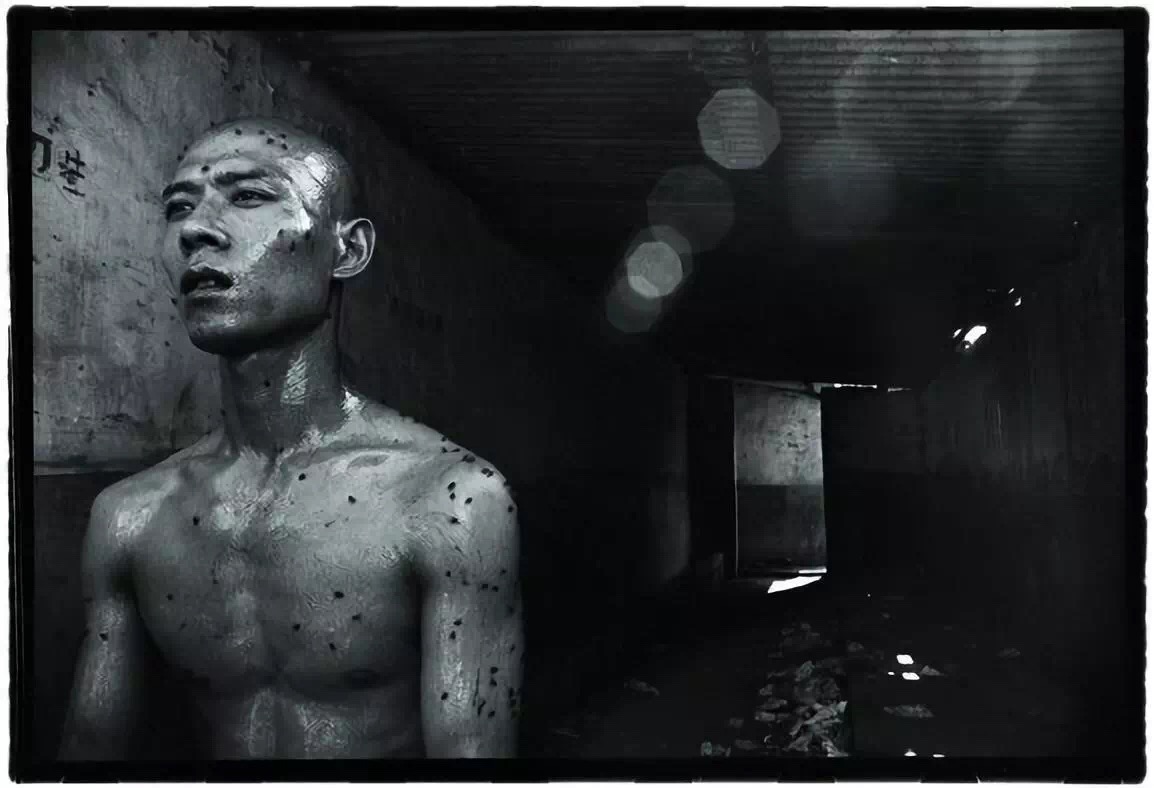

Taking the Beijing East Village as its impetus, the White Cube demonstrates how Chinese artists and photographers intensely and collectively explored the multiple expressive possibilities of photography. One of the most radical innovations of photography in the early 1990s was an aggressive emphasis on the nude human body, a motif rarely found in traditional Chinese art. “The Body as Language” articulates the ways that artists such as Zhang Huan and Ma Liuming deployed the camera to document performances that tested the limits of the body, explored the changing sense of self in modern China, and confronted aspects of the country’s history and culture.

The symbolic power of the nude body continues to surface in surprising ways, as in Lu Yang’s Delusional Mandala (2015), Chen Lingyang’s 25:00, No. 2 (2002), or Lin Tianmiao’s Go? (2001). Such works underscore Zhang Huan’s belief that “the body is the only direct way through which I come to know society and society can come to know me. The body is the proof of identity. The body is language.”

Some of the works exhibited in the White Cube refer to historic artworks and artifacts from China’s 2000-year cultural heritage. Through expansive and sprawling compositions, the artists in “Revisiting and Recasting the Classics” update and synthesize classical, historical imagery to comment on contemporary issues. Ai Weiwei’s triptych Dropping a Han Dynasty Urn (1995) depicts the calculated destruction of a centuries-old urn. Wang Qingsong’s Night Revels of Lao Li (2000) is an ironic updating of a celebrated, thousandyear- old scroll painting. Hong Lei’s diptych Autumn in the Forbidden City (1997) alludes to the delicate bird-and-flower paintings of the Song Dynasty and mourns the passing of an era of high artistic sophistication. Qiu Anxiong’s recent animation New Classic of Mountains and Sea III (2017) is an ambitious reworking of a classic Chinese literary text.

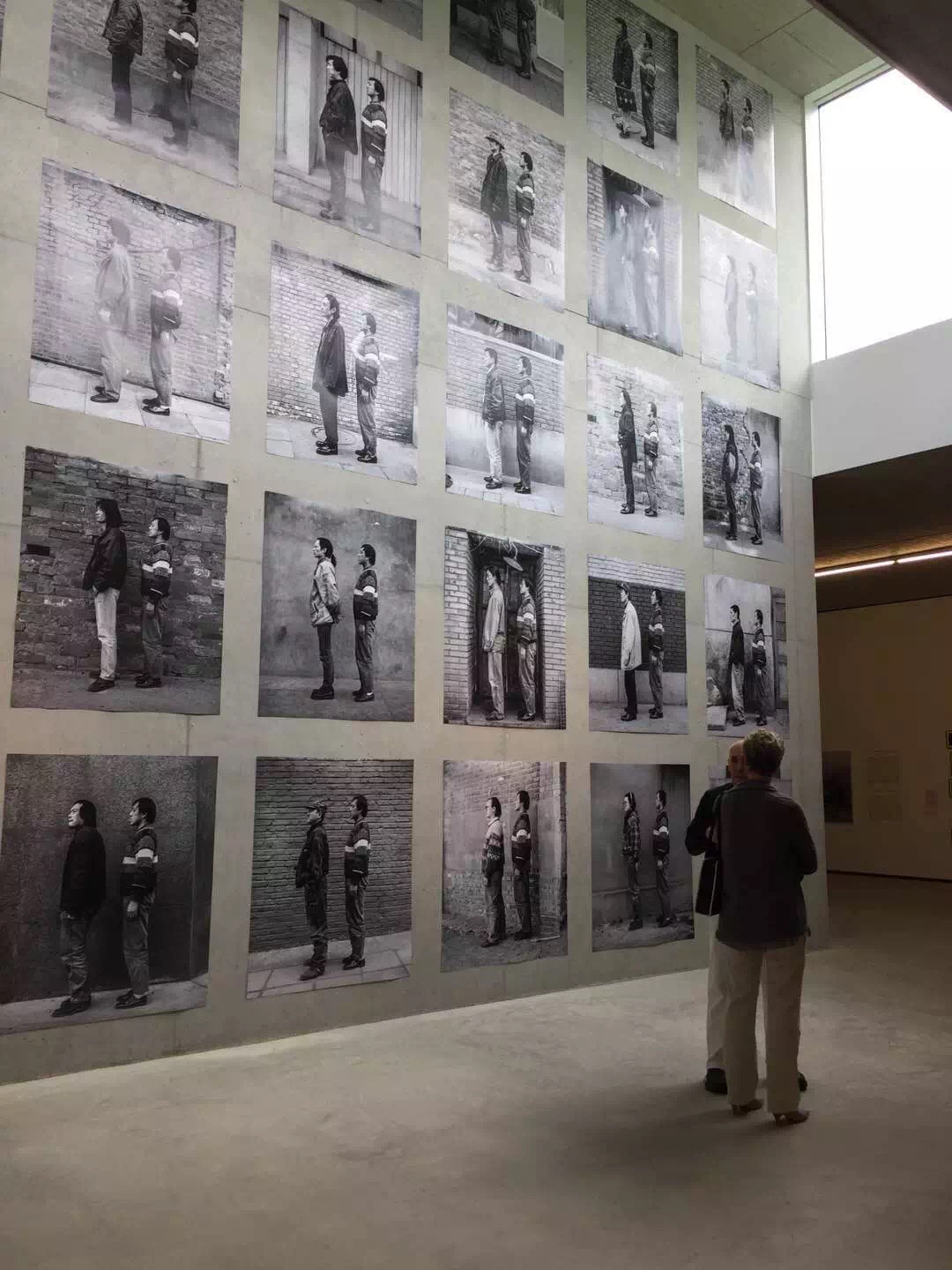

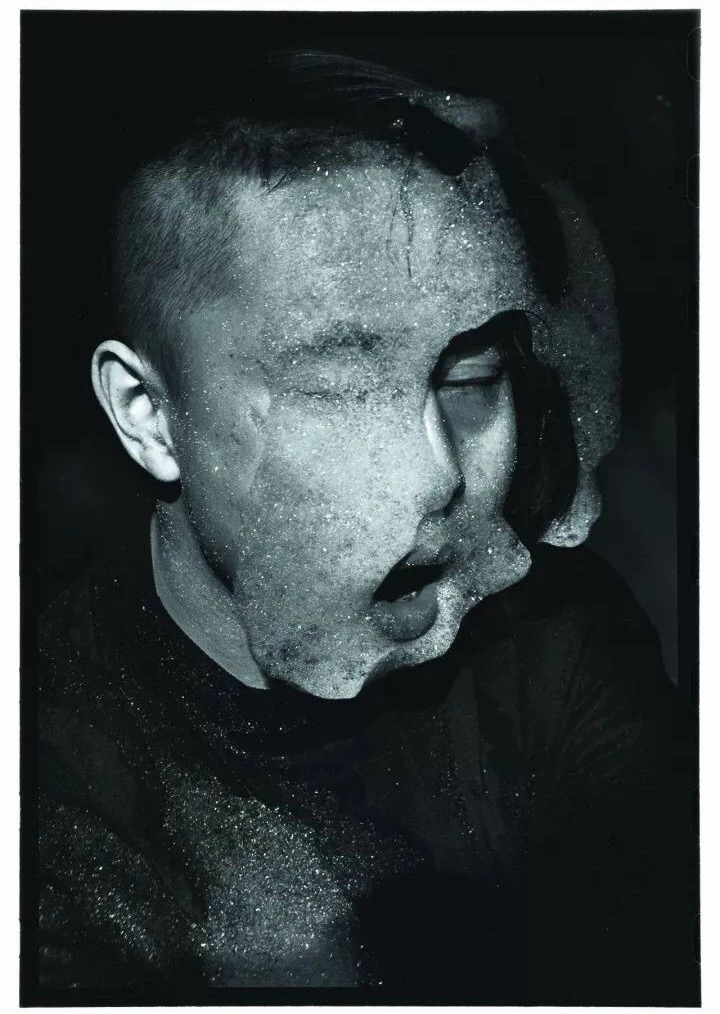

荣荣 RongRong, 东村 East Village 1994 No.1

荣荣 RongRong,东村 East Village,1994.No.20.

Surveying, examining, and intervening upon the architectural and built environment, the artists in “Urban Utopias and Dystopias”—also shown in the White Cube—present a variety of ways to consider the tensions embedded within the physical structures of urban China. Works by Zhang Dali, Luo Yongjin, Xiang Liqing, and Sze Tsung Nicolás Leong reflect the demolition of long-established urban neighborhoods in Beijing and Shanghai, in order to make way for high-rise developments. The emptying out of rural villages by migration to the cities forms the backdrop of Yang Fudong’s stark video installation East of Que Village (2007). Employing six video screens, the artist provides a grim, but engrossing tour of his desolate childhood village.

While many aspects of daily life have undergone tremendous changes since the country officially launched its reform and opening policy in 1978, the Chinese Communist Party has been able to maintain its monopoly of power through authoritarian-dictatorial style of government. Producing artworks that offer explicit political commentary continues to be dangerous in China, but such works are still being made (if not shown) there as the Black House documents. Mo Yi’s 5.16 Notice: It’s Been 49 Years (2014) is a large-scale grid of found photographic images of Mao Zedong during the years of China’s devastating Cultural Revolution; the images are covered with the artist’s handannotations in red paint. Using a casual, essayistic style, Bo Wang’s video China Concerto (2012) explores the effort by the Chongqing city government to revive and update Mao-era propaganda practices in the early 2000s. Sheng Qi’s Memories (Me) (2000) shows a close-up of the artist’s hand cradling a tiny photographic portrait of himself as a child. It’s impossible not to notice that his little finger has been cut off—an act of self-mutilation carried out, purportedly in response to the 1989 bloodshed in Tiananmen Square.

荣荣 RongRong, 东村 East Village,1994.No.81(12_12)

In the early decades of the People’s Republic, China’s social structure officially consisted of a solid core of workers, peasants, and soldiers. The more fluid and transient social formations that define contemporary China are reflected in the Green House in “New Personal and Collective Identities,” with the emergence of various forms of individual and collective identity based on gender or sexual orientation. Xu Yong’s serial photographic work This Face (2011) traces the repeated changes in self-presentation carried out by a female sex worker over the course of one day, as she carefully fashions a new persona for each of her clients. Zheng Guogu’s The Life and Dreams of Yangjiang Youth (1999), which inspires the title for this exhibition, depicts the artist’s close circle of friends playfully reenacted scenes inspired by Hong Kong TV and movies that had just became available in the small Southern coastal city of Yangjiang. In an immersive, dazzling video accompanied by an anime and scifi-influenced soundtrack, Lu Yang’s Delusional Mandala (2015) narrates the hyper-realistic journey of Lu’s 3-D counterpart, an asexual avatar going through the processes of enlightenment, brain surgery, and a funeral procession in free-floating cyberspace.

荣荣 RongRong, 东村 East Village,1994.No.70(10_12)

Life and Dreams does not set out to provide a full account of the many facets of Chinese photography and media art that have developed over the last three decades. Instead, it offers a selection of works that represent diverse, challenging, and complex individual perspectives. Although its core consists of the extraordinary photographic works made during the 1990s, the exhibition goes beyond offering a fixed view of that crucial chapter in the development of photography and media art in China. The simple passage of time has a remarkable power to throw older works into new relief, bringing out qualities that would have been imperceptible at earlier moments. In addition, placing earlier photographic works in the company of recent examples of Chinese media art allows for surprising echoes, affinities, and continuities to be revealed.